In 2014, just before I got engaged to my wife, we watched the first season of the show True Detective, and I was completely taken by Matthew McConaughey’s character Rustin Cohle.

Cohle is a pessimist — not a half-assed Eeyore pessimist who just looks at the glass half empty, but a philosophical pessimist, someone who thinks the existence of humanity is a mistake. He gives a particularly miserable speech at one point in the show, while talking with his detective partner Marty Hart.

RUST: I think human consciousness is a tragic misstep in human evolution. We became too self aware; nature created an aspect of nature separate from itself. We are creatures that should not exist by natural law.

MARTY: Hm. That sounds god fuckin’ awful, Rust.

RUST: We are things that labor under the illusion of having a self, a secretion of sensory experience and feeling, programmed with total assurance that we are each somebody, when in fact everybody’s nobody.

MARTY: I wouldn’t go around spouting that shit if I was you. People around here don’t think that way. I don’t think that way.

RUST: I think the honorable thing for our species to do is deny our programming, stop reproducing, walk hand in hand into extinction, one last midnight, brothers and sisters opting out of a raw deal.

MARTY: Man, I picked today to get to know you. Three months and I don’t get a word out of you —

RUST: You asked.

MARTY: Yeah, and now I’m begging you to shut the fuck up.

Spoiler alert, if you haven’t seen that particular season:

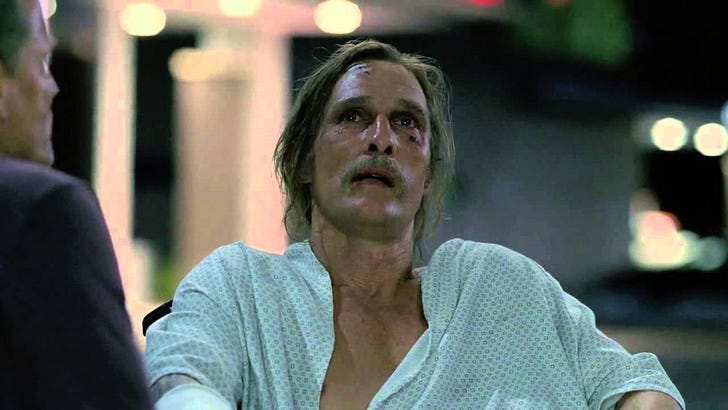

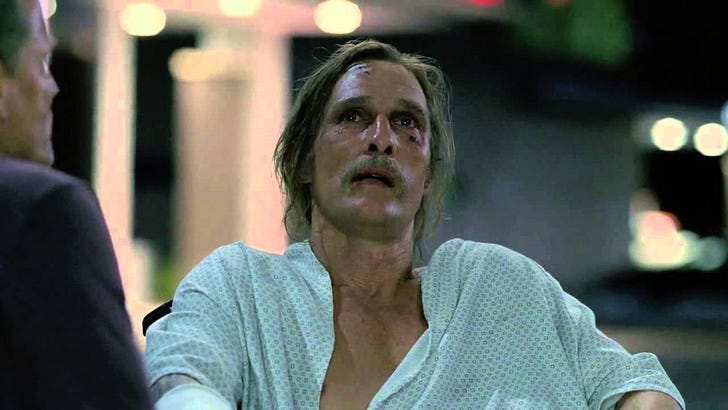

At the end of the season Cohle gets stabbed and has a near death experience that gives him a change of heart. He doesn’t become an optimist, per se, so much as he has hope that there are things worth fighting for, that life is worth living.

I had to leave our apartment and take a walk after we finished the final episode. The truth was that I was feeling more philosophically in line with the Rust of the earlier episodes, and as much as I loved the show, I suspected it had opted for a happy(ish) ending rather than a perfectly satisfying one.

But, I thought as I walked, if I believed this: what was I doing? The engagement ring was already in my apartment, I just hadn’t gotten down on one knee yet — was that the right move if I didn’t actually think life was worth living? Worse, Steph and I had decided to have kids. Was that even moral given what appeared to be the planet’s catastrophic trajectory?

Anti-natalism and the philosophy of despair

After I finished True Detective, I got a copy of Thomas Ligotti’s The Conspiracy Against the Human Race. The book was cited by True Detective’s showrunner Nic Pizzollato as one of the core inspirations for Cohle’s character. It’s a philosophical tract by a reclusive horror writer arguing that humanity is a mistake, that existence is (he always puts it in all caps) MALIGNANTLY USELESS, and that to have a child is to commit an act of violence.

Unfortunately, I found his arguments convincing. I read this book just as we moved from Washington, DC, to New Jersey, and it was one of the reasons I entered a long period of depression that I have yet to completely pull out of, nearly 9 years later.

Advocates of the anti-natalist movement argue that life is mostly suffering and pain, and that as such, creating life is to effectively add more suffering to the world, and is immoral. They argue that we can’t take care of the people that we have on earth, that the planet is getting overpopulated, that humans are actively destroying the planet and other life, that human consciousness is a horrifying mistake, and that if we wanted to contribute the greatest good, we would all commit to voluntary extinction.

On the tail of this, I read Paul Ehrlich’s The Population Bomb, the 1960’s environmental tract arguing that humans need to do an enormous amount to curb population growth if we want to have a sustainable future. Ehrlich argued for mass sterilization programs in the Global South, where more population growth was happening, which he believed should be incentivized by rich western governments as a condition of humanitarian aid. It was a tough choice, he believed, but it was our only chance of survival as a species.

Then 2016 happened, the night of our one year wedding anniversary. Donald Trump was elected, and on that night, I said to my wife, “We can’t have kids. We can’t bring them into this. We’re fucked.”

In early 2018, my daughter was born.

Light vs. Dark

What changed my mind, ultimately, was also True Detective. In the final lines of the show, Rust and Marty discuss the battle of light vs. dark. Marty looks up at the sky, and says, “Seems to me the dark’s got a lot more territory.”

Rust tells him he’s looking at it wrong: “Once, there was only dark. If you ask me, the light’s winning.”

In the context of the show, I didn’t know if this was a satisfying conclusion — I wasn’t sure they’d done the work to get Rust to that point. But in reading about the line, I learned that it had been almost lifted word for word from a comic called Top 10, by my favorite writer, Alan Moore. I’d loved his books V for Vendetta and From Hell, but on the heels of True Detective, I checked Top 10 out from the library and then proceeded to read everything the man had written that I could get my hands on.

Once I’d read all of Moore, I got a hold of any book which he’d recommended in an interview, and read those, and out of them, I was able to cobble together a philosophy in which I didn’t have to abandon my atheism, but in which I also didn’t have to succumb to the nihilism of the anti-natalists.

With a broader reading of Alan Moore, these are two lessons one absorbs:

* Good vs. Evil is a distraction — it is something we spend our entire lives wringing our hands about, whether good will win out in the end. In reality, good and evil require one another. You can’t have a hero without the villain. So the day evil is defeated, good will cease to exist. As Moore puts it in his fantastic Saga of the Swamp Thing, evil is the decaying mulch that good grows out of. And if one must exist for the other — can anything truly be said to be right or wrong?

* What matters is the current moment. We can spend all of our lives worrying about outcomes, but in Moore’s cosmology, time is eternal: all moments past and present exist simultaneously. Our experience of consciousness is much like reading a book: we’re currently focused on a specific word or sentence, but that doesn’t mean the pages we’ve already read have stopped existing, nor does it mean the future moments also don’t exist. There is actually some good science backing this view, but it’s effectively just a mind-bendy and psychedelic way of saying what everyone from the Buddha to Garth from Wayne’s World has been saying for eons: Live in the now.

Peeing as an act of hope

What changed my mind on having kids was this: Even if the anti-natalists arguments are internally consistent about how terrible life is, about the meat-grinder that is the world, they aren’t able to tell my that my personal experiences are all pain and misery, because they aren’t: I actually enjoy most moments of my life.

I am not in a state of constant pain. I go for walks and I see birds and that feels nice. I wrestle with my kids and they give me big hugs and their hair smells vaguely of hay and little kid sweat. I do stretches in the morning and it feels incredible. I eat delicious foods and sip delicious drinks. I smell coffee before I drink it, watch the cream swirl in beautiful chaotic clouds, and then get to sip at it. At night, I crawl under my cool covers in my cold room and I just squirm for a few minutes because it feels so good. And — NO ONE EVER TALKS ABOUT THIS — I get to go to the bathroom and get to pee! Peeing feels fantastic! It’s just a moment of intense relief I get to feel like, 6 times a day! And pooping?! Stop! It’s just an embarrassment of riches!

In my depression, I had stopped paying attention to these sensations, but once I began to do so again (thanks, edibles!), I realized just how constantly the world was serving me wonderful stimuli.

Beyond physical sensations, the evidence of most of my interactions seem to directly contradict the nihilists’ “people are trash” arguments. Grocery store check-out clerks are usually kind to me. Strangers on the street smile at me more often than they frown or yell at me. My friends are kind and funny and fun to be around. Occasionally, I come across a jerk (or, more accurately, a person who is having a bad moment) but with just a little bit of knowledge about humans’ inherent negativity bias, I began to understand that these encounters actually just absorbed more of my attention than the pleasant ones, which were in reality far more frequent.

The question — is it fair to bring a child into this world? — forces you to ask yourself: are you happy to be in this world? I was born in 1986, during one of the scariest parts of the Cold War. My parents could easily have decided the very real possibility of nuclear armageddon was reason enough to not bring another child into this world.

I would not say history has gone particularly well since then, but I’ve also managed to have a mostly enjoyable, fulfilling life in that time. Ultimately, it is up to every individual person to decide if their life is worth living. But the evidence seems conclusive: each day, most people don’t commit suicide. Most people find life worth living. The anti-natalists argue that this is because of a glitch in human consciousness, but who cares if the happiness you feel while scratching a dog’s tummy is a glitch? It still feels nice. We could use more glitches like that.

More than that — most of the people who espouse this sort of view suffer from severe depression and anxiety. The question I’ve learned to ask during my fight with depression is: what came first? The depressing thought or the depression? Is the planet a meat grinder of despair, or do I just need to go for a walk?

I do not always have an answer for this, but it certainly seems to me that my children’s natural state is to be happy. Darkness always creeps in to human life, but so do beauty and joy, and it will be up to my kids to decide what they pay attention to.

None of this means that people should or shouldn’t have kids. That choice is up to the individual, and if we’re being honest, there needs to be more space and acceptance of people who choose not to have kids — those of us with kids depend on them pretty heavily for both support and fun. But it does mean that maybe the fact that we’re scared about the future isn’t an adequate justification for instituting global eugenics programs that sterilize the poor. We could always, instead, change our political and economic system to one that isn’t consuming the planet, and try to live in balance with our world rather than wring every resource dry so the worst humans can have even more wealth. All we need to do to keep population in check is just average two kids per woman. There are plenty of ways to do that voluntarily instead of the eco-fascist “kill the poor” strategies of Ehrlich and his cadre.

Even if we are coming to the end of human history (I don’t believe that we are) I suspect that the odds are in my favor in betting that the final human’s final thought will be a nice one.

Better Strangers is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

This is a public episode. If you would like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit betterstrangers.substack.com